Gaze Inside Me: Ex-Machina and Life Itself as Information

The near obsession to peer into the depths of the human body as a way to understand the complexities of life is a familiar one if we pause to think about it. Almost every day, molecular biologists tear into the walls of human and animal cells to investigate the genes in our DNA in hopes that it will help us better understand how our body works to keep us alive. This obsession to look into ourselves, however, is not completely new. The early 20th century saw the growth of techniques of looking at and into cells in order to make the inside of the body visible. In doing so, looking at cells became the same as looking into "life itself." It was through the socio-political and scientific changes such as the one brought about by Ross Harrison, who isolated living cells outside the body, as well as Alexis Carrel and Burrows who made the technique of "culturing life" outside possible and helped establish "tissue culture" around 1910, which is still a core technique of much biological research today.*

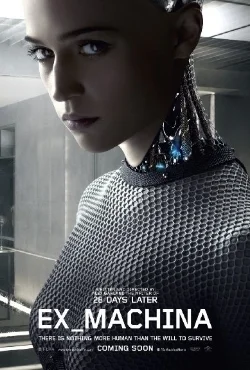

And this obsession to look inside in search of answers about ourselves is not limited to a small group of elite scientists. Through the porous boundary that separates the world of science and society - or "our real world" - the work of probing the inner depths is a familiar practice for most all of us. It is, then, not a great surprise that the movie Ex-Machina also attempts to open up the bodies to the viewers' eyes to answer a philosophical question : "What makes us human?" which is intimately related to the question, "What is life?" or "What constitutes human life?" Any attempt to answer these questions will inevitably be quite reductive and so I cannot claim to know the answer to the questions.** To say that one can answer such a question would be ahistorical as well as dogmatic and dangerous. Ex-Machina's own vision about "life itself" gives us an entry point into a historical wisdom that will help us be on guard against any claims of transcendental knowledge about what constitutes life. And this is what I hope to discuss here: What kind of vision about life is Ex-Machina proposing? Where does such a view come from? When can we say that such a view arose? In short, the antidote to self-assured answers about the notions of life is a historical inquiry into how discussions and concepts about life come about.

Ex-Machina directed by Alex Garland tells a story about a mega-rich IT company owner, Nathan Bateman, who brings in one of his company's employees, Caleb Smith, to administer the Turing test on his latest iteration of his female artificial intelligence (AI) product that he named Ava. The test, Caleb and Nathan tells us, is to determine whether or not this creation is really an AI. In Caleb's words, "When a human interacts with a computer and if the human doesn't know he is interacting with a computer, the test is passed." That is, a human should be "fooled" into thinking that the robot or computer is actually a human. The significance of such a feat - of having replicated humanity or having created life itself - is not lost to Caleb who claims that Nathan would have attained a near-god status and thus, be written into the book of "the history of gods." With the story now set, the entire movie revolves around Caleb administering the Turing test. There is, of course, a twist to the plot. The viewers find out that in reality, Caleb was not administering the test - he was the test. Nathan wanted to see how Ava would try to use Caleb (and not the other way around) in order to escape the narrow underground laboratory "she" was created in and into the real world of humans. According to him, the creativity involved in solving the problem of how to escape would be the real measure of a machine being an AI.

The most interesting moment of the movie for our discussion is the first time Caleb meets Ava. As she walks out of her isolated room into the hallway towards Caleb, who is separated from "her" by a translucent but a near indestructible wall, the viewer sees what looks like a hybrid of computer, robot and human. Ava's chest is metallic, but it was structured to resemble a woman's breast. When we gaze at Ava's face, her eyes, lips, and synthetic skin makes her look so real, so human. In fact, when Ava later covers her body by wearing a dress that nearly covers all of what appears to be her robotic components, it is hard to tell that she is in fact not human. However, our eyes are immediately drawn to her abdomen: it is translucent and displays what looks like metal cables that regularly flashes lights and colors as electric impulses travels through her "veins." Immediately, Ava, I conclude, is not a human. She is the result of cables and computer codes that mimics humans, but can never be human. She is just an aggregation of information placed inside her brain that makes her act and think like a human.***

But, then again, isn't this what humans are after all? Aren't we just a bunch of information?

The movie certainly thinks so. The Turing test that is central to the plot is about measuring information processing and flexible adaptation by re-interpreting a set of information Ava has "learned." Although Nathan has gone to the real trouble of creating a body that resembles the physical attributes of a human, the core - or the "soul" - is the mind. You can mimic the skin perfectly, but for Nathan, what really matters is if his creations can think and act, through the information she has, like a human. This emphasis on information as the core of life is thus really unmistakable. His first gesture to the question from Caleb about Ava's creation is to show him her "mind": a blue spherical object harboring the information downloaded to it from the queries that humans have posed in the search engine his company owns. Ava is defined by the information her brain. Ava is information. As such, Ex-Machina argues to us that the soul of life - life itself - is information. It is an informatics paradigm of life: life is defined in terms of information content.

That life is an agglomeration and series of information is a historical product. The notion that life is information arose around the 1960s as a result of World War II (WWII) and the 1950s shift toward new information technologies and communication science that accelerated through the Cold War. Government investment in research dramatically increased in the 1940s. Pushed by Vannevar Bush, the head of the Office of Scientific Research and Development and a scientists himself, money poured into research to create a post-war society based on science and technology - a practice that by then had become familiar as large research projects had been funded for war efforts. The crucial need for communication during WWII, and the ensuing Cold War, stimulated the production of new knowledge about coding and decoding messages. This gave us the famous works on information theory by Norbert Weiner and Shannon that now is the foundation of common gadgets and public infrastructure today that we take for granted, including the internet and mobile phones. With history encouraging an information based science and technology research and society, it is not strange that such a way of thinking would also inform investigations about life and biology and bringing in concepts like "feedback loops" that were characteristic to information theory to explanations about life processes.****

The application of an informatics theory and language to describe biological functions and life itself was a substantial shift from previous theories and practices. In the decade that preceded the explosion of information theory in biology, explanations about body functions were described in terms of biological specificity. The most easily grasped concept about biological specificity is the lock-and-key model of enzyme and substrate: each enzyme has a specific 3D structure that specifically corresponds to one specific substance (that is, its substrate). Briefly, it means that there were specific and unique correspondence between structure and function, differences between species, etc. which was attributed to specificity of proteins. The concept of specificity was both a result of ongoing discussions about how the body's different parts worked together as a whole (for example, the arm, legs and torso working together in harmony) as well as the 20th century changes that was pushing toward industrial modernity. The latter had brought about an emphasis on specialization of labor (for example, I paint the car while another person puts the car together) and also worries about social order. This is partly why Rockefeller Foundation was so interested in investing money into research of heredity - they wanted to relieve the social chaos by scientific research of heredity that would help them control the type of people that would populate society. If, as Thomas Huxley believed, everything in life was determined by the biological substance (at the time, proteins; see next paragraph), knowledge and control of heredity would mean control of life in the broadest sense - both heredity and society. In short, the discussions about part-to-whole relationship and the ushering of industrial modernity influenced how our bodies and its life functions were imagined before the beginnings of the information paradigm by using the the language of specialization, specificities and order.

We should also note that at the time, protein was still considered as the center of life (not genes or DNA). To understand this notion, we have to briefly forget about what we know about current theories of genes and DNA. The research they had done until then pointed to proteins as being the master substances that allowed life to happen: evidence said they were key components of bodily structures and acted as enzymes as well. In this way of thinking, protein was life. Nudged by such insights, the proliferation of protein studies brought about biological specificity into a brighter spotlight and because of its supposed importance as master molecules of life, it influenced talks about the genes. I have to caution here that what they called the gene is not what we now think of as the gene. At that time, what "genes" were was still being debated - some thought that genes were also just proteins. Specificity of species and biological function still resided in the most important molecules of life at the time - the protein. But the still debated identity, structure, and function of this thing called "gene" didn't mean they didn't talk about what the gene was or its importance in life. And thus, gene talk was also part of scientific discussion - science requires you to ask different questions, after all, even about things you don't know yet.

For instance, scientists George Beadle, before adopting information theory, introduced what we now know as the one-gene-one-enzyme theory. In this formulation, one gene controlled one specific reaction, which in turn was controlled by one specific enzyme. If you take a close look at this sentence, there is no talk about genes "holding information" or "directing" things to happen. They described the genes as providing some form of physical attribute (the exact word would be "complementarity") that imposed a specific character on the resulting folded proteins. In a sense, the gene was a director that "stamped" - as Joshua Lederberg described it - the physical characteristics on proteins. Still, specificity of the species and biology - that is, what made a species different, for instance - was still found in the proteins. It wasn't until later, most notably by the work of French scientist Monod, that specificity of life would shift to DNA. It might be hard for us today, and rightfully so, to understand how this is different from the gene being reservoirs of information. A crude comparison might be that the genes were like physical molds that you could shape things on. They were not, for instance, a sentence that you could read that contained directions - which is the way we conceptualize DNA today. But the specific identities of the proteins is what made life unique.

With this historical knowledge in mind, one can now see that Ex-Machina's formulation of life as information is also shaped by this information paradigm of life. Talking and imagining about life as information proliferated with works on information theory and technology in both military and civilian research. As such, this information framework became a popular, convincing, and seductive framework for a new generation of scientists and public to actively adopt against other competing concepts of life. And it must be noted that this shift toward and information paradigm was never smooth nor linear: other theories competed with it, sometimes overlapped, sometimes ably criticized the new view. Even different forms of thinking about the information paradigm of life existed. What is important for us to know here, however, is that the incorporation of the information paradigm into biology shifted scientific works and the resulting discussions and thoughts about our bodies and life in the language of information. This is very evident in the way we take as given descriptions about biological parts of our lives: the DNA is conceptualized as hereditary information; the brain and the nerves are thought to transfer information; hormones are messengers. And thus, the core of what makes us human in this sense is the storing, processing, passing on, and adapting various information. Ex-Machina shows us how pervasive and seductive this framework is as it assumes that life as information for its audience is a given starting point. But we know now that it was a more historical work filled with contentious competition to get here, balancing theories of what elemental life is composed of (e.g. proteins or genes) and figuring out how to imagine and talk about it (i.e. biological specificity or information theory).

The conversation here is not to definitively determine whether being human is about the information we contain. What I can say is that the attempts to define life itself and the core of what makes us human in terms of information is a historical product, as shown by our inquiry into the movie Ex-Machina. There are other questions that the movie raises, like is the "soul" of the human to be found in the "mind?" Is is then fair to say that the "mind" is what makes us human? Those questions are incredibly fascinating, but perhaps, deserve to be answered in another post.

Notes:

*For a more in-depth understanding about the debates concerning the notion of life in the biological sciences, Culturing Life by Hannah Landecker and Beyond the Gene by Jan Sapp provides excellent accounts about the discussion about the separation of life from the body and the reproduction of life

**Even a short discussion problematizes any single answer: for instance, when you look after the mid-20th century, life was firmly thought to reside in the gene or DNA. But as scientists entered the 21st century, the cell arose again as being the smallest foundational unit of life

***You could say that this is an alternative formulation of Lacan's mirror in which you get to know who you are when you look into the mirror. In short, Lacan's work shows that the idea of who you are comes from the external world and its myriad of discourses, problems, ideas and ideologies that are reflected onto you. As such, the way you get to know yourself is not independent from the socio-political and historical circumstance in which you are born. But now, instead of a mirror, we are making our bodies transparent to gaze into ourselves to get to know who we are.

****A more thorough discussion about the turn toward an informatics paradigm of life is found in Who Wrote the Book of Life? by Lily E. Kay